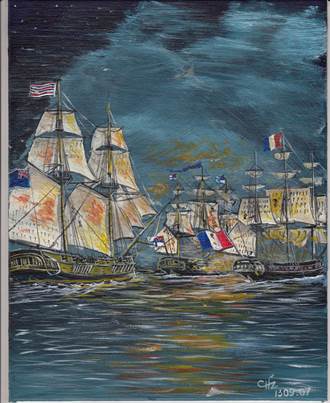

Cover art for Sailing Dangerous Waters: Another Stone Island Sea Story

The Long Wait

A rivulet of perspiration trickled down Edward Pierce’s forehead and

threatened to flow into his left eye. He

squinted, changing the contours of his face so the sweat dripped off the tip of

his nose. As the drop fell free, the persistent fly that had harried him for

the past half hour landed on his right cheek.

He swatted at it, ineffectively.

“We should rest. I believe Tom grows weary.” Pierce was one of four men moving easily

through the glade, balancing the desire to keep moving with the need to

rest. Towering evergreens blocked the

February sun’s brightness but did little to ease the heat felt at their

roots. No breeze cooled those moving

through the undergrowth. Other creatures

had sense enough to wait for the evening’s relative coolness.

“I’m quite all right,” Tom Morgan

panted from the rear.

“Edward is right.” In the lead, the Original Vespican’s diction

and accent strongly contrasted with his appearance. Darker than the others, he wore a

breechcloth, linen leggings, and deerskin moccasins. His uncovered hair fell loosely about his

shoulders. Two nondescript feathers were

woven amongst its strands.

“If we are in no haste,” asked Isaac

Hotchkiss, “why do we push so?”

“I must say, you learn quickly. I’ve seen those raised on the edge of the

wilderness not master life here as quickly.

That you are seamen amazes me that much more.”

Seafarers or not, the three seemed

accustomed to life in the forest.

Baltican in appearance, they dressed more completely but similarly to

their guide. In the afternoon’s heat,

none wore more than buckskin trousers and homespun linen shirts. Pierce and Isaac Hotchkiss sported old

misshapen round-brimmed hats. Tom Morgan

wore a fur cap, complete with the striped tail of the creature. He walked with a noticeable limp and worked

harder to maintain their leisurely pace.

“We have an excellent teacher,”

replied Pierce. “And Isaac is right to

wonder about our haste.” He swiped

half-heartedly at the fly.

Tom sank gratefully to the ground in

spite of insisting he wasn’t winded. The

three carefully leaned their muskets against a nearby stump. The leader’s rifle, a fine precision made

firearm was also within quick reach.

They weren’t hunting, nor did they fear any immediate danger. Still they remained alert, not knowing what

threat might materialize out of the deep forested groves.

“The only haste is on Tom’s part, I

feel,” said Isaac. “Were I enroute to

see someone as dear as she, a little afternoon heat would not stop me.”

“Nor would a missing

leg, Mr. Hotchkiss.” Tom twisted

and stretched, the wooden end of his right leg clattering against an exposed

root.

“Does it pain you, lad?”

“Not at all, Doctor. I believe it has healed completely over the

past months. A bit of fatigue from

continual movement is all it is.”

“Do I examine it and be assured? Perhaps the stump is not callused enough for

such a prolonged journey.”

“If you choose to,

sir. But any aches I feel are due

the awkwardness of movement and not any tenderness.”

“Then I will forego a look, Tom. But you must promise to notify me of any

additional discomfort.”

“Of course, Doctor.”

“Edward,” said Isaac, addressing the

second individual. “Is this similar to

your search for the herbs needed to treat Tom’s leg?”

“Yes, but we were mounted and did not

roam so far away from the settlements.

I’m sure Lord Sutherland was more troubled then because I was out of his

immediate control.”

“With your behavior over the past

months, and my own minute influence, I believe he is more at ease with your

current absence,” said Doctor Robertson.

The four drank moderately from the

water bags they carried. Silence ensued

as each became lost in his own thoughts.

Edward Pierce took his rest stretched

out on the soft carpet of the forest floor, his eyes closed and his breathing

slow. But he was not asleep. His active mind and the ever present fly

would not allow it.

Several months ago, Pierce had been

quite despondent, depressed by the capture of his vessel, HMS Island Expedition and its internment by

the Tritonish Consulate in Brunswick, New Guernsey. He had also been very worried about the

health of Tom Morgan, the schooner’s senior midshipman, who wounded in the

battle with HRMS Hawke had his leg

amputated. Healing had proceeded

normally until a deadly infection set in.

The schooner’s surgeon, Doctor Matheson, and one called in by the

consulate, a Doctor Blackburn, had been unable to halt Tom’s

deterioration. Then Doctor Robertson had

arrived, and with a combination of modern Baltican and ancient Kalish

medicines, reversed the trend towards the midshipman’s ultimate demise.

With Tom Morgan on the mend, and with

Doctor Robertson’s assurances that as a Vespican Unity Congress delegate, he

would work to obtain the release of the schooner and her crew, Pierce had found

himself in a much cheerier state of mind.

But that had been in September of 1803.

Now near the end of February, 1804,

Pierce knew that the Baltican educated, half Rig’nie doctor was making his best

effort, but progress was slow. Island Expedition was still tied up at

the pier in Brunswick’s harbor, guarded by marines from the Tritonish Consulate

and Vespican militia. While he and his

crew were treated most cordially by the Consul and his staff, and indeed by the

local Vespicans, they were restricted in their activities. Pierce and Hotchkiss his first lieutenant

were not permitted aboard the schooner at the same time. Only a third of the crew was permitted aboard

on any given day, as a way of insuring the vessel did not put to sea. That of course would have been a foolhardy

venture, as the schooner was moored deep within the harbor, and would have had

to pass by many Tritonish flagged merchantmen, which upon word from the

consulate could easily prevent an escape to the open sea. At times there were also various Tritonish

warships in the harbor, the presence of which, further

prohibited any rash attempt to leave.

As the months slowly passed with no

resolving their predicament, Pierce slowly lost the optimism that Doctor

Robertson’s initial appearance had brought.

It should have been easy to see that the crew of Island Expedition was not a band of Galway Rebels and Pirates. Perhaps the sticking point was in convincing

the Tritonish that they had come from a different world to locate a lost and

legendary island. Had he not experienced

it himself, Pierce could see where such a tale would be unbelievable to those

hearing it. Now he wanted most of all to

sail from the Vespican port where they were held, return to the island, see to

the colonists’ wellbeing, and eventually return to England.

Pierce had grown more morose, and as

his spirits had declined, his shortness with consulate staff and schooner’s

crewmembers had increased. Finally, when

word was received that HRMS Furious

would arrive to take on supplies and affect repairs, Doctor Robertson suggested

some time in the wilderness. Following

their capture by the Tritonish Navy’s Flying Squadron, Furious had served to transport Pierce and Hotchkiss to

Brunswick. It had also escorted and

guarded Island Expedition as it

sailed to the same port under a prize crew.

Pierce particularly detested Lowell Jackson, captain of the frigate, who

was an exceedingly rigid disciplinarian.

He routinely meted out the severest and cruelest punishments to his

crew. If in Jackson’s

presence again, would Pierce be able to control the rage within and refrain

from bodily attacking him?

He had agreed wholeheartedly with the

doctor’s suggestion of a small wilderness expedition, cumulating in a visit to

the doctor’s Kalish people. He would not

have to face the hated Jackson, nor see Leona with him. Pierce did not love her, but the situation

would have been awkward. Both Jacksons,

husband and wife, were known for their lustful wanderings. While she complained privately of his, he

jealously suspected, and perhaps rightly so, every man who might be even

innocently in her company. If he did not

directly challenge any such individual, he often worked in the background to

bring the unfortunate person to personal, financial or professional grief. The frontier journey was the best solution

for Pierce’s safety.

Doctor Robertson stirred, stood up,

shouldered his bag, and picked up his rifle.

“We should push on a bit more. We

are near the river and will camp there for the night. If fortunate, we find a canoe in which we

might continue our journey to Shostolamie’s village.”

The four reached the river in the

early evening and encamped for the night.

The next morning they searched for, and after a short time found a

serviceable canoe a few hundred yards upstream.

Pierce was concerned that taking the

craft might be theft. “No,” replied

Doctor Robertson. “It is unmarked. Those who left it do not intend immediate

reuse. Kalish custom is that such

equipage is for all. Should one require

its subsequent use, he would place his personal totem on it. Then we would know the canoe is reserved.”

“An amazing display

of trust, Doctor.”

“Indeed, Isaac. Many values and beliefs of the Original

People differ from those of Balticans, or in your case, Europeans. Traditionally we are not so concerned with

individual possessions. Most things

belong to all. We will use this canoe to

reach my father’s place. Someone else

will then use it for another journey and leave it for yet another party.”

That day they paddled upstream against

the gentle current. The river was broad

and flowed easily so they did not need to overly exert themselves. Nevertheless, when they rested along the

river at night, they were sore from bringing unused muscles in to play.

Early the next afternoon they spotted

smoke from several cooking fires blanketing the tree tops beyond the next river

bend. Doctor Robertson guided the canoe

to a smooth beach upstream of the large Original People’s village. On the open water they were spotted

immediately, and their guide mentioned that they had no doubt been observed and

their progress followed since early that morning. As the sharp prow of the canoe grated on the

sand, Pierce and Hotchkiss jumped out.

Lighter now, it floated free and the two remaining aboard gave a final

tremendous stroke with their paddles.

Pierce and Hotchkiss grabbed the gunwales and hauled the craft farther

up the beach. The doctor got out and

helped steady it so that Morgan could climb out.

A large crowd of children, many of

them naked in the afternoon heat gathered around. They pressed close to Doctor Robertson and

shouted with good-natured joy. The

children did not fear the Englishmen, but having never met them; avoided

getting too close. The youngster’s noise

set the dogs to barking, and soon the entire village was awash in the canine

din. At the racket’s crescendo, the

older children and adults abandoned their normal routines and headed for the

beach and the recently arrived party.

While Pierce could not fathom the

words, he could tell by the expressions that this was a joyous occasion, and

that as guests of the doctor, they were welcome. Many greetings and well wishes were exchanged

by the doctor and the village inhabitants.

Then the crowd quieted and a small party of important villagers made

their way forward. Pierce had met some

before and easily recognized them.

The old man, his hair turning gray,

the lines and wrinkles beginning to dominate his features, still moved with

dignity and bearing, even though he was attired only in a breech cloth,

moccasins, and woven grass cape.

Feathers dangled, seemingly at random from his hair, and leather bands

encircled his upper arms. Doctor

Robertson approached him, made a small gesture of respect, and the two formally

embraced. The old man said something that brought a smattering of laughter from

the crowd.

The old man cleared his throat, a

habit Pierce remembered, smiled broadly, and said. “Now here smart man. Ha! Ha!

Drink coffee like Dream Chief.

Him plenty smart! Bring coffee,

Edward Pierce?”

“Of course, Revered

Shostolamie, Dream Chief of the Kalish People.”

“Son teach

you good, Edward Pierce.” The old man shook

Pierce’s hand vigorously. “Shostolamie happy see Hotchkiss!” he

said and shook his hand as well.

“Happy

see Morgan. You still alive! Son good doctor!” Shostolamie laughed, shook Morgan’s hand and

clapped him on the shoulders.

An older white woman stood close by

the Dream Chief’s side.

“Mother!” said Doctor Robertson. They embraced, first in the manner of the

Kalish, and then in a more Baltican fashion.

“It gives me joy to see you again.”

“As it does me, my son,” she said.

“Gentlemen, may I present my mother,

Alice Madison, wife of Dream Chief Shostolamie.

Mother, please say hello to Commander Pierce, Lieutenant Hotchkiss, and

Midshipman Morgan?” begged the doctor.

“Your servant ma’am,” said Pierce,

followed closely by similar expressions of greetings from the other two.

“I have heard much about you from the

good doctor, your son. I am honored to

finally meet you.”

“And I you, Edward. May I call you ‘Edward?’”

“I would be honored, ma’am.”

“But you must call me ‘Alice.’ Or ‘Mama Alice,’ if the first doesn’t fit

with your ideas of social decorum.”

“Of course, ma’am,” responded

Pierce. He was about to correct himself

and add “Mama Alice” when another group of villagers pressed gently into the

circle. Of these, Pierce recognized

Bessie and her daughter Cecilia. The

younger was Doctor Robertson’s protégé and assistant, and had nursed Morgan in

his recovery.

Night Fisher, the doctor’s cousin,

Bessie’s husband, and Cecilia’s father was with them. His Kentish was on a level with Shostolamie’s

and he greeted the Englishmen with sincere but abrupt warmth. He spent an extra minute sizing up Morgan,

but soon gave the one-legged midshipman a grin and pumped his hand vigorously.

Bessie beamed at Doctor Robertson,

greeted him in the Kalish fashion, and allowed herself a quick smile and a

perfunctory hand shake with Pierce and Hotchkiss. Then, as was her habit regarding younger men

in the presence of her daughter, she scowled.

But when she turned to Morgan, her smile was wider and it lasted

longer. She warmly embraced him in the

fashion of her people, and surprised, Pierce saw the midshipman return the

gesture with practiced ease.

Cecilia said hello to her cousin in

the traditional way, and then acknowledged the presence of Pierce and

Hotchkiss. “I’m very glad to see you

both again,” she said in near perfect Kentish.

“I hope you enjoy your stay.”

“I am sure we shall,” said Pierce.

Then the young lady knelt before

Morgan, her face full of joy and her eyes filled with tears of happiness. She spoke in Kalish, and whether the

midshipman understood or not, Pierce did not know. Morgan knelt as well, facing her with an

equivalent look of happiness on his face, and spoke several lines of

Kalish. There were murmurs of approval

from the crowd, and a few good-natured chuckles, as Morgan had trouble

pronouncing some words. She reached for

him in a variation of the ritual she had used to greet her cousin. He responded to her movements, having been

coached by the doctor, or perhaps by Cecilia those many weeks ago in

Brunswick. Their movements, their

gestures were slow and stately, a well-choreographed, traditional means of

greeting someone very special. The

formal, proscribed part of the greeting ritual over, the young couple melted

into a warm embrace.

“Everybody meet! Everybody happy!” shouted Shostolamie. “We eat!

Edward Pierce, drink coffee. Shostolamie

drink coffee!”

Pierce could not sleep that night in

spite of the large and delicious meal they had been served. The bed, in the fashion of the Original

People was comfortable, clean and airy, and he should have fallen into a deep

slumber the moment he laid down. Had he

consumed too much coffee? He often drunk

that much or more and never had a problem sleeping. No, he decided after several hours of

wakefulness, coffee was not the problem.

He was thinking of things that kept him awake, things that he usually

did not dwell on as he fell asleep.

When Doctor Robertson had suggested a

wilderness excursion to keep him out of harm’s way, he had invited Hotchkiss

along as well. Pierce’s childhood

friend had always expressed an interest in the lives of American Natives, and

Robertson understood the similarities of the Original Peoples and the Indians

of North America. He thought Hotchkiss

would benefit in spending time with them.

All were aware of the deep relationship that had developed between Tom

Morgan and Cecilia as she had nursed him back to health. It would have been a tremendous affront to

either, not to have included the midshipman in the visiting party.

All this explanation was perfectly

ordinary and straight forward in nature.

At this level, everything was as it seemed, and as it was intended. He was happy to be in Shostolamie’s village,

away from Jackson and his possible rage should he suspect any improper

relationship between Pierce and his wife.

Hotchkiss was ecstatically happy to experience even a brief moment of a

life he had read about since childhood.

And Morgan, of course, was extremely happy and very lucky to be with

Cecilia once again.

That was the problem, and it became

clear to Pierce as he lay quietly, breathing slowly, his eyes closed, feigning

the appearance of sleep, but in reality, wide awake. Morgan had the opportunity to be with the one

in his heart. How Pierce wished to be in

England at that very moment, wrapped with passionate joy in Evangeline’s

embrace! That he wasn’t, and that he

wanted so much to be with her, pained him greatly. Perhaps Morgan’s present happiness made his

aloneness all that more acute! Did his

friend’s great joy magnify his loneliness and make it that much more

unbearable?

With sleep unable to overtake him,

Pierce’s mind raced through the night.

He fought not to think too much of Evangeline, and tried to focus on the

present situation regarding his vessel and crew. Could they ever convince the Tritonish

officials they were not Galway Rebels?

At times, he thought they were close to believing him. At others he felt he might as well try to

make a river to flow upstream. Their one

hope lay with the Vespican Unity Congress and then the Vespican Joint

Council. Doctor Robinson, a Unity

Congress delegate had been pressing the issue, and Pierce had been somewhat

upset to find the doctor away from the Bostwick sessions. Earlier that evening he had somewhat bluntly

brought forth his objections to the doctor.

“But we have other pressing matters as

well,” Robertson explained. “Try as I

may, I cannot keep debate focused on your plight. With the coming of summer, the Congress and

the Joint Council have both adjourned.

Many delegates have obligations they must attend to at home. There are short sessions in the latter half

of February, but they are largely ceremonial, the seating of new delegates and

the like.”

“It is disappointing, Doctor,” Pierce

replied, “To know that nothing is being done at the moment.”

“I do understand, and believe me,

Commander, were the Congress meeting today, I would not be in Shostolamie’s

village. Rather, I would be pressing for

a resolution regarding your internment.

However, neither the Congress nor the Joint Council do anything more

than get acquainted in these current sessions.

There are speeches, ritualistic events, and dinners, sir, but no actual

work ever gets done during the summer sessions.

When cooler weather arrives, perhaps in May or June, then the real work

occurs. When it does, please rest

assured that I’ll be there on your behalf.”

The pallet next to Pierce

rustled. Hotchkiss stirred and sat

up. Then he stole quietly from the lodge

and into the warm moonlit night. He

returned a few moments later, crawled onto his bed, and tossed about

momentarily. From the sound of his

breathing, he was soon asleep again.

While he and

his crew enjoyed a quite benevolent detention at the Tritonish Consulate, and

the honest hospitality of the Vespicans, the fact that they were trapped more

than a world away from home, gnawed a small but growing hole in Pierce’s

stomach. He was, however, grateful that

Doctor Robinson had established a precarious correspondence with Harold Smythe

and the other Englishmen on the island.

At least they had an idea of the predicament that Pierce and Island Expedition’s crew found

themselves in.

Thinking of that made Pierce wonder if

it was proper for the most senior officers to be away on what could be

described as a holiday. He did not doubt

the abilities of O’Brien the master, Dial or Spencer, master’s mates, or

Andrews the second senior midshipman.

But was he remiss in his own duties to have left them on their own?

No, it was better he avoided Jackson

while Furious was in port. Should he regard Pierce’s absence with

suspicion, he would be told that Pierce and the others had accompanied the

convalescing Morgan, who sought to regain his strength in the wilderness.

As the eastern sky lightened with the

coming of the new day, Pierce finally fell asleep.

The three Englishmen remained in the

Kalish village until the end of March.

Then reluctantly they set out to journey back to civilization. Pierce missed the lazy idyllic days of

hunting, fishing, and learning the ways of nature. Some days he had done absolutely nothing,

other than drink coffee and talk with the Kalish Dream Chief. But Pierce was aware of his responsibilities

and knew he must return to Brunswick, his crew, and the interned schooner.

Hotchkiss had filled two journals with

notes as he had enthusiastically experienced the day-to-day lives of the

Original People. He too regretted

leaving, but like his captain, he knew his duty required him to return.

Leaving was hardest for Morgan. His weeks in Shostolamie’s village had been

as near paradise as he would probably ever be.

There were tears in his eyes, and tears in Cecilia’s eyes as the three

seamen and Doctor Robertson paddled downriver.

A week later they were back in

Brunswick. Pierce and Hotchkiss resumed

their residence at the Tritonish Consulate, each in the very room he had

occupied upon arriving the previous July.

Morgan, at his insistence now berthed with the other midshipmen and

warrant officers. His stump had healed,

and as he was pronounced fit by the doctor, he did not rate a private room.

Pierce was relieved that no serious

problems had arisen during their absence.

The visit by HRMS Furious had

been anti-climatic. There had been words

between Jackson and his wife, and the former had spent much of the port visit

in the company a local woman of somewhat shady reputation. Yet, true to his nature, Jackson had

questioned his wife’s romantic activities prior to his arrival. To Pierce’s immense relief, he had not come

under suspicion, but a military aide at the neighboring Gallician Consulate

had. The young Gallician had looked too

long and lustfully at Mrs. Jackson, and the captain had accused him of being

her latest paramour. It could not be

proven true or false and diplomatic considerations between two warring nations

in a neutral country further complicated matters. While Jackson openly flouted his tryst with

the Brunswick woman, he did not actively pursue satisfaction regarding his

wife’s suspected indiscretions.

Practically speaking, Pierce was

thankful for the latest of Jackson’s lustful interests. Had he not been so involved with her, his

probing and suspicious mind may have deduced the connection between Pierce and

his wife. He chided himself for ever

having been involved with Leona Jackson.

Such a relationship, in spite of the physical pleasures, was not

necessarily worth the attendant problems.

Another effect of Jackson’s somewhat

lengthy port visit was that all Brunswick was afforded a view of his stentorian

disciplinary means. Unlike many

Tritonish Navy captains, Jackson did not permit his crew liberty while in

port. He was afraid of desertion, and

having seen firsthand the rigid and brutal means by which he controlled his

men, Pierce would not have blamed them.

It would have served the bastard well if half the crew had run.

It took only a few days for Pierce to

settle into what had been, and what would once again become routine. He made his visit aboard Island Expedition every third day.

He attended various dinner and supper parties, hosted by well to do

Brunswick merchants, bankers, and officials, or those hosted by either the

Tritonish or Gallician Consuls. He took

no real pleasure in these affairs, other than the chance to ascertain the

current level of hostility between the two nations. He also used these events to gage the

resentment held against both by the local Vespicans, whose own nation was insultingly

trod upon at every instance.

He thought to break off the

relationship with Leona Jackson, and for several weeks after his return, saw

her only at the various dinners. But

when she knocked at his door late one night, the temptation was too great, the

physical needs too intense, and she remained with him until the early morning

hours. After she left, and as he lay

exhausted, he wondered if he should refuse her renewed advances. Would rejecting her wantonness cause her to

become a vengeful, deadly foe, who sought to destroy the one who had so

recently been her lover?

The weeks passed by slowly, but soon

it was May and the first snows came. On

that particular day, Pierce shivered as he left the schooner and walked through

the half-melted snow. He had planned to

return directly to his room at the consulate, but the thought of a warm cup of

coffee or even a glass of rum entertained him.

He made up his mind, reversed his steps and headed for the Frosty

Anchor. That establishment had become a

second home to Pierce and indeed all the hands from the English schooner.

Humphrey the owner greeted him as he

entered. “Coffee is fresh,

Commander. A cup, do you think?”

Pierce stamped the snow off his

feet. “No, not today, I’ve had more than

enough. But do you have it; a brandy or

rum would surely warm a body.”

“Aye, it would. Now you look positively frozen. Sit here, close to the fire and I’ll fetch a

glass for you.”

Pierce sat at the table, soaking in

the heat of the roaring fire and all the while feeling the brandy, which he

sipped slowly, spread its own warmth within him. He was slipping back into his despondent

angry mood, and the weather certainly did not help. He tried to bury the frustration and anger in

the back of his mind and appreciate the niceties of his current situation. He was deep in somewhat meditative thought

when the voice broke through.

“Commander! Commander!” said Doctor Robertson with some

urgency. “I had waited for you at the

consulate, believing you would return there.

But I cannot say I blame you in stopping to warm up.”

A workman at the end of the counter

looked at the doctor with contempt but said nothing. Perhaps he felt that the doctor, despite his

prestige and well-made Baltican clothing did not belong in even such a place as

the Frosty Anchor. Some Vespicans had

very little tolerance for Rig’nies in their midst. The doctor caught the glance and ignored

it. Humphrey saw it as well and glared

at the man, who soon turned back to his mug of ale.

“It is a raw day, Doctor. The weather fits my disposition, and I sought

to warm them both.”

“In that case, Edward, I have news

that may warm your spirits as well. I

depart in the morning for Bostwick. The

Unity Congress resumes session next week, and I will go once again to put forth

your case.”

“That indeed is good news, sir. Now, will you have a glass with me?”

“Indeed, sir!”

“Then I must return to the

consulate. I’m expected at a late dinner

and do not have the means of begging off.”

“Obligations have their rewards,

Commander, as well as their distractions.”

“Aye.”

Pierce finished his second glass of

brandy and accompanied by Doctor Robertson, made his wet and snowy way back to

the Tritonish Consulate.

©2008 by D. Andrew McChesney